An illustrated argument against the urban big box

So Mayor Daley vetoed the big box ordinance. And he got the three aldermen he needed to switch sides in order for the veto to stick. I disagree with his position, but that's the way it goes. Da Mayor gets what he wants. But what really sticks in my craw is what I read in the newspaper today. According to the Chicago Tribune, Mayor Daley commented on how there has not been such opposition in the suburbs, and he suggested that the ordinance "will unfairly keep stores out of black city neighborhoods."

Now there is some irony in trying to bring race into it, since African-Americans, given their history in this country, should be particularly sensitive to being under-compensated for the work they do. As for the Mayor's claim that the ordinance keeps big box stores out -- that simply is not true. At most, it might provide a slight disincentive to opening stores here. But there are other reasons aside from employment issues for opposing big box development in the city. In my previous entries on the subject, I've focused on the economics; at risk of turning this into a New Urbanist manifesto, allow me to demonstrate why Wal-Mart and its ilk make for poor urban design and should therefore be discouraged from building stores in urban areas. (There might also be legitimate reason to oppose big box stores in the suburbs, but opposition would not be effective without regional coordination among suburbs.)

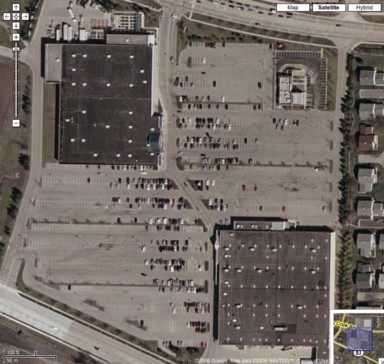

Take a look at Figure 1. This is a aerial view of a Wal-Mart (upper left) and Sam's Club (lower right) in the Chicago suburbs near where I work. A McDonald's restaurant is at upper right. Each side of the image is roughly a quarter mile.

Figure 1: Typical Wal-Mart and Sam's Club in suburban setting

Now look at Figure 2. This is a aerial view of the Jewel grocery store in my neighborhood. (For readers in other parts of the country, a Jewel is similar to an Albertsons or a Publix.) The scale is precisely the same as in Figure 1: the photo is a quarter mile on each side.

Figure 2: Jewel (Albertsons) supermarket in urban setting

The Jewel represents relatively low density compared to its surroundings, yet its presence does not disrupt the urban street grid. It is located close to mass transit (note the buses lined up south of the parking lot, within 150 feet of an elevated train stop). Its parking lot is relatively full, indicating minimal waste, and those who live in the surrounding residential buildings need not even drive there. Just within the area shown, there exist approximately 1,000 residents. The Jewel coexists well, even if it is not a perfect design.

In Figure 1, the Wal-Mart, you can see some single-family housing on the far right. I would estimate that fewer than 40 people live in the area shown, not including the suburban homeless who might spend the night in their cars in the Wal-Mart parking lot. There is no street grid, and what might appear to be a rudimentary grid in the residential area (really modified cul-de-sacs that double as driveways) is totally disconnected from the shopping that is so tantalizingly close! The owner of the house with the brown roof might walk out his back door for a gallon of milk and have only an eighth of a mile walk to the front door of the Wal-Mart -- except a fence prevents him. Instead, he must get in his car and drive three quarters of a mile and park just a couple hundred feet from where he started.

That gallon of milk might be twenty cents cheaper at Wal-Mart than at the Jewel shown in Figure 2, but that doesn't include the hidden costs of: the necessity of owning a car; the wear and tear on the car of approximately $.10/mile; the cost of fuel of approximately $.10/mile; and so on.

You might suggest that he walk on the sidewalk, but there are a few problems with this. First, the nearest sidewalk, near the top of the image, is inaccessible from the adjacent residential area. It connects to a subdivision farther to the east, but that subdivision is not within easy walking distance. It is a sidewalk to nowhere. Not surprisingly, I hardly ever see anyone using it.

But even if Mr. Brownhouseguy could get to the sidewalk, he would still feel an aversion to walking on it. It is a featureless white strip in the middle of a space that is poorly defined. To one side he looks out over a sea of parking (most of it empty), and to the other he is confronted with four lanes of traffic whizzing by at 55 miles an hour. The experience is more like being on the open savannah (complete with the cheetahs) than in a place conducive to human life.

While this is but one example, I'm sure millions of suburbanites can recognize the environment depicted in Figure 1 as being functionally similar to those they encounter every day, and containing the same dysfunctional qualities. Much of the dysfunction boils down to the fact that the suburbs are designed for cars and not for people.

Wal-Mart stores are built on the scale of suburban sprawl -- not on an urban scale. If big boxes like Wal-Mart are built in urban places, they must either be put in the few suitable areas that are far from the most vital parts of neighborhoods, or they must be built to a smaller, denser, more urban scale. Otherwise, their presence damages the built environment of the neighborhood.

2 Comments:

mark, well stated. I should come to your blog more often

Thanks, Peter (a.k.a. dad-e-O).

Post a Comment

<< Home